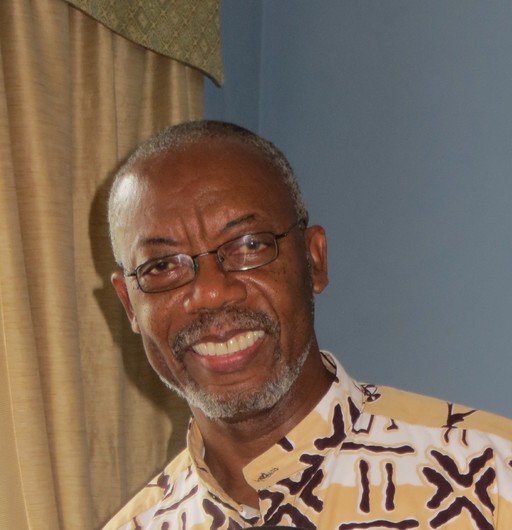

by

Dr. Anderson Reynolds

This discourse is divided into four parts. The first part speaks to how Allen Chastanet has served as the mirror on the Wall for racial issues. The second part looks at how Allen Chastanet’s rule has brought our National Identity Crisis to the fore. The third part shows how Allen Chastanet has served as SLP and Philip J. Pierre’s best friend. And the last section speaks to how Allen Chastanet’s rule may have inadvertently sparked a St. Lucia cultural awakening.

Part 1. Allen Chastanet, The Mirror on the Wall

In a previous missive, I noted that Allen Chastanet was a blessing in disguise, to which several St. Lucia Labour Party (SLP) patriots took offense because they said I was looking for excuses for the former prime minister, I was letting him off the hook; I was condoning the misadventures of his administration. But could it be that the SLP stalwarts were being shortsighted or disingenuous?

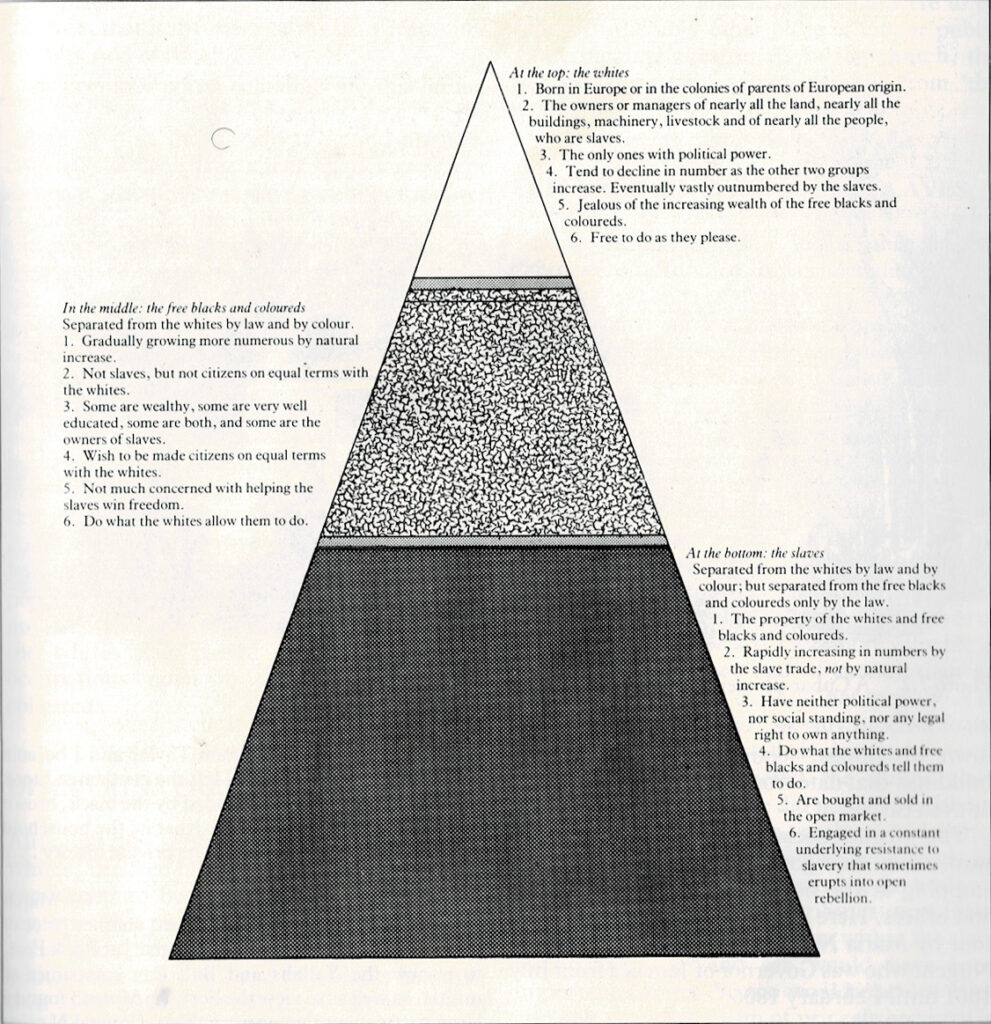

Before the rule of Allen Chastanet, the non-white St. Lucian majority had seemingly left their slavery past behind and were going about their merry life of racial harmony and tolerance. After all, the professionals and people populating most government and private sector positions looked no different from them, few were fully aware that the white minority still owned a disproportionate share of the country’s wealth, most had no memory of a white St. Lucian politician, much less memory of the days when the white minority planter and merchant elite dominated both the economics and politics of the country; and to avoid the pain and shame associated with the country’s slavery days, most were ever so willing to bury the past and let bygones be bygones. A recent study by Shearer on memories of Caribbean slavery suggests that much: St. Lucians often choose to bury the past, because they find the history of slavery too painful and shameful to revisit.

Then in came Allen Chastanet, a non-St. Lucian born, politically of the incorrect race, culturally speaking barely St. Lucian, seemingly running roughshod over the laws and statutory institutions of the country, showing little regard for its sovereignty and cultural and natural patrimony, and displaying a lack of sensitivity and appreciation for its historical and cultural milieu. And suddenly the clock turned back to the era of the slave plantation system social hierarchy and with it a return to racial anxiety, feelings of inferiority, feelings of a loss of nationhood and identity.

Suddenly, Allen Chastanet became the mirror held up in front of St. Lucians, exposing their self-hatred, illuminating their shameful past and their shame of feeling inferior, and giving deference to white people, unearthing discomforting feelings buried deep under generations of layers of pathos and self-denial. It was as if Allen Chastanet was the fruit from the tree of knowledge that, like Adam and Eve, made St. Lucians suddenly realize they were naked, they had been living a lie that race didn’t matter and was of no consequence to neither their internal nor external lives. So should we blame the mirror or the fruit for showing us what was already there?

The experience of many Africans, including Nigerian novelist, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, is that they only began thinking of themselves as black when they came to America, a country that, in her book Playing In The Dark, Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison characterized as a “wholly racialized society”. Before then, they thought of themselves as say, Igbo, Nigerian, African, but never black as a separate identity.

Similarly, before Atlantic African slavery, the notion of a white race or the notion of Europeans as a separate identity was nonexistent. Europeans labeled themselves in terms of religion and ethnicity or tribe (French, English, Irish, etc.), but never as white or European, even. It was in juxtaposition to the black, unfree people of America, of the Atlantic world, that the notion of a white race came into being, and the notion of America, meaning white and free as opposed to nonwhite and enslaved, was born.

So it seems in juxtaposition of the perceived outrageousness and whiteness of Allen Chastanet—the worst prime minister in St. Lucia’s history, according to some—St. Lucians suddenly realize they are black. And some previously staunched Labour supporters who had long distanced themselves from the party suddenly became Labour stalwarts once again. Chastanet had helped sharpen the battle lines and apparently made people rediscover they are black and St. Lucian and African and they are in danger of losing it all, losing their St. Lucian-ness

Apparently, before Chastanet most St. Lucians thought they were living in a raceless bubble, in which they were untouched by race and racism. Racism was something that took place in faraway America and the once-upon-a-time apartheid South Africa. Well, Allen Chastanet seemed to have burst that bubble. The undeniable truth is that we are living in a racist world, in a white man’s world, where most people accept, know, that black people are inferior to all other races, where every nonblack person knows he is inherently superior to any black person, where even the black people themselves accept their ascribed inferiority—neg mezawab (niggers are miserable), neg modi (niggers are cursed) , neg mova (niggers are wicket), neg pa sa vive asemb (niggers do not get along), neg ti pli mova nacion (niggers are the worse people on earth).

How could they believe differently when around the world everything screams black inferiority—war-torn starving Africa, China colonizing Africa and the Caribbean, African-Americans last placed in almost every socioeconomic statistic? American police gunning down black people as if black lives are worth even less than the paper the US constitution (supposedly safeguarding their rights as citizens) is written on. African Americans hardest hit by COVID. In the time of COVID, China forced Africans out of their apartments and onto the streets. According to some human rights organizations, Africa has the highest prevalence of modern slavery. No black country has nuclear weapons, meaning yellow or white skin people can wipe out the black world without a whimper of retaliation.

The surprise should not be that black people have bought into their ascribed inferiority, the surprise should be finding a black person who hasn’t.

Part 2. The National Identity Crisis

Allen Chastanet presented St. Lucians with an existential crisis. And crisis forces change, and paradigm shifts. Allen Chastanet forced St. Lucians to confront issues that go to the very heart of who they are as a people. To begin with, Allen Chastanet forced St. Lucians to dwell on issues of national identity. What did it mean to be a St. Lucian? Who was a St. Lucian? What constituted a St. Lucian? Is a St. Lucian defined based on skin color? Meaning, does one have to be black or non-white to be accepted as a bonafide St. Lucian, in the manner that according to Republicans (Apartheid South Africa) only a white person can be truly American (South African)? Given the country’s history of slavery, can a white person be truly St. Lucian? Or is a St. Lucian defined based on culture, meaning one’s St. Lucian-ness depends on the extent to which one is an integral part of St. Lucian culture? If so, what exactly is St. Lucian culture? Or is a St. Lucian defined based on a set of shared values and beliefs, if so, what are those values and beliefs?

In defining a St. Lucian based on color, the descendants of African slaves need to be careful, because the St. Lucian creole whites—the Devauxs, Chastanets, Duboulays, Bergasses, etc.—may beg to defer. They can argue that the Caribs aside, they are the real St. Lucians; they were the first to tame and colonized this land, they were there before the Africans and before the East Indians. In brief, they are more St. Lucian than most St. Lucians. Or they have just as much or more right to be St. Lucian as any other. Indeed, they imported the Africans and later the Indians to labor on their plantations. And they have proof, for while most blacks can only trace their lineage back to a few generations (in fact, most can’t even trace their lineage to slavery), the white creoles can trace their lineage going back millennia. For example, in his book A St. Lucian Family, Ian De Minvielle-Devaux traced the lineage of the Devaux family to Roman times. Michael Chastanet has many people laboring for him, but does that mean it is the laborers and not Michael Chastanet who owns the businesses? Clearly, in St. Lucia’s court of law, if not its court of justice, the creole whites would win the St. Lucian nationality primacy case hands down.

It is not even clear that the black population is prouder to be St. Lucians, prouder of their St. Lucian heritage and patrimony than do the native white population. It is Robert Devaux, the great chronicler and researcher of St. Lucian history and natural patrimony, who we have to thank for a full documented account of the exploits of the Neg Marons in their fight for freedom and their assertion of their African-ness. The first and only comprehensive history of St. Lucia is written not by a St. Lucian but by Dr. Jolien Harmsen, a Dutch national who has adopted St. Lucia as her home, and of whom some may say has gone native. If we look more closely, we may discover that entities such as the National Archives, the Historical and Archeological Society, and The National Trust, which are directly involved in preserving our natural and historical patrimony, were initially spearheaded by white St. Lucians. For example, Robert Devaux was the one who established the National Archives, and he was a co-founder of the National Trust and its first director. The M&C Fine Arts Awards, of which cultural icon, Jacques Compton, said: “not since the demise of the St. Lucia Arts Guild had an enterprise become so responsible for the veritable flowing of the Arts in St. Lucia,” was the Devaux’s independence gift to the nation.

Now, that’s not to say that the black population hasn’t been involved in preserving our heritage and patrimony. The Folk Research Center renamed The Msgr. Patrick Anthony Folk Research Centre, which has probably done more than any other entity in preserving and championing our folk heritage and helping to instill in us an acceptance and appreciation of who we are, was founded by our cultural priest, Monsignor Dr. Patrick Anthony. And some may quickly point out that given slavery and the white population’s continued monopolization of the economy, the above-mentioned contributions are the least they can do. But the main point is that the black population doesn’t have a monopoly on love of country and of preserving and enhancing our patrimony, so that can’t be used as a basis for not fully embracing the white population as St. Lucians.

Besides forcing St. Lucians to confront their blackness, Allen Chastanet forced the populace to consider what kind of St. Lucia they want. Is it a St. Lucia populated with high rises and resorts but in which St. Lucians are bystanders, strangers in their own country, second-class, third-class citizens, subservient to a class of lately come foreigners enjoying the best of what the island has to offer, thereby by creating an apartheid society, the ghettoization of the country? Or is it a St. Lucia where St. Lucians are full participants in the development process, where development is primarily about people and not simply about infrastructure buildup, and where St. Lucians feel at home and have a strong sense of nationality, sovereignty, and that this island is their country, and is working primarily in their best interest?

Many books have been written on how Europeans were able to rise and dominate the world. We are in the epoch of the Europeans. So it’s no surprise or mystery that we are living in a white man’s world. It isn’t even surprising that black people have internalized their ascribed inferiority. After all, self-confidence isn’t developed in the abstract. It is acquired through reinforcement. Besides, internalizing our ascribed inferiority had or has survival value. What is baffling is that we have been actively contributing to our inferiority, and we are not doing some of the obvious things that would help arrest our inferiority complex.

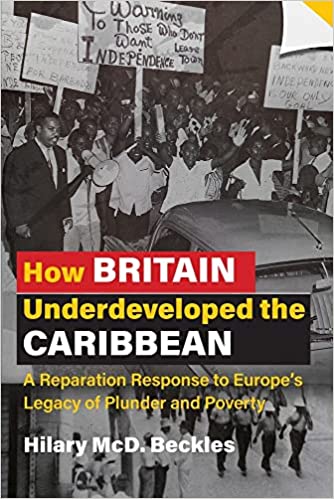

We speak of the great evil of slavery that white people imposed upon us. We think of our enslavement as the greatest of human stains. We see around the world, and not just in America, that black people continue to be under threat. In many different ways we are being told that black lives don’t matter. Our fists are raised in demand for repatriation. Our slavery past continues to color our existence and define our culture and who we are. Yet we are happy with the queen of England as our head of state. The queen graces our dollar bills. The Privy Council, and not the Caribbean Court of Justice, continues to be our Court of last resort as if we have more faith in the justice of the white man whom we accuse of committing against us the greatest injustice the world has ever seen.

Here is a thought in passing. Our enslavement was such a great evil that several hundred years later we are still traumatized by it, so then why are we so silent about the continued enslavement of our African cousins?

Knowing and understanding where we came from and how we got to the present would be a first step to regaining our mojo, building our self-confidence, chipping away at our self-contempt. But how will that happen when history isn’t even a compulsory subject at schools, and often, when we teach history, it is history that focuses on the glorification of our enslavers and colonizers, history that shies away from our glory days, history that does not honor our heroes. For example, how many St. Lucians are aware that their 1950s St. Lucia Arts Guild sparked a cultural renaissance during which St. Lucia was the leading light in West Indian theatre and out of which emerged some of St. Lucia’s and the Caribbean’s most renowned cultural creators?

Come to think of it, isn’t it ironic that many St. Lucians were ashamed and vexed to have an almost white man as their prime minister, so much so that in their eyes Allen Chastanet could do or say no right—the worse prime minister in St. Lucia’s history—and many of the things they accused him of may have gone unnoticed if he was unquestioningly black, yet these same St. Lucians are quite happy to have the Queen of England, the epitome of whiteness, imperialism, and an emblem of their enslavement and colonization, as the head of their country, superseding their prime minister, adorning their currency.

There is now a Caribbean outcry for reparation for slavery. But in my mind there are two parts to the call for reparation. First, the making of amends for the wrong that was committed, meaning providing damage compensation; and second, taking steps to repair the damage that slavery wrought. Most of the focus on reparation, however, has been on the first part—monetary compensation. Much less attention has been paid to repairing the damage slavery brought about. Probably the most enduring consequence of slavery is the psychological damage of self-loathing, self-contempt, and inferiority complex, which can be addressed through education, art and culture, the teaching of history, the honoring and celebration of our accomplishments and heroes, and yes, through symbolic acts and gestures that signal that we truly believe, we truly are on par with any other people from any part of the world. Having the Queen as our head of state and the Privy Council as our court of last resort, either way, is of little material consequence; but of great symbolic value, signaling our continued inferiority complex.

Recently, there was uproar in the region over Royal Visits to commemorate Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee, marking the Queen as Europe’s longest-serving monarch. The sentiment that echoed throughout the region was: How dare the Royal Family make official feel-good visits to our country when the monarchy and the UK government have ignored CARICOM’s call for reparation and full and formal apology for slavery and its accompanying genocide?

But, however valiant the protest, it was misdirected. Constitutionally, we are the Queen’s subjects, so the Queen and her surrogates have every right to come and survey their dominion and appraise their subjects. The public’s aghast should have been directed at their governments and their political leaders and ultimately themselves (since they are the ones who elect their representatives) for failure to constitutionally remove the Queen as head of state. The public should have welcomed and exploited the Royal visit as a tourism promotional tool and then confront their government for its complicity. But on second thought, if fundamental change only occurs from the ground up, maybe the public uproar may serve as a harbinger of change.

Part 3. Allen Chastanet is Philip J. Pierre’s Best Friend

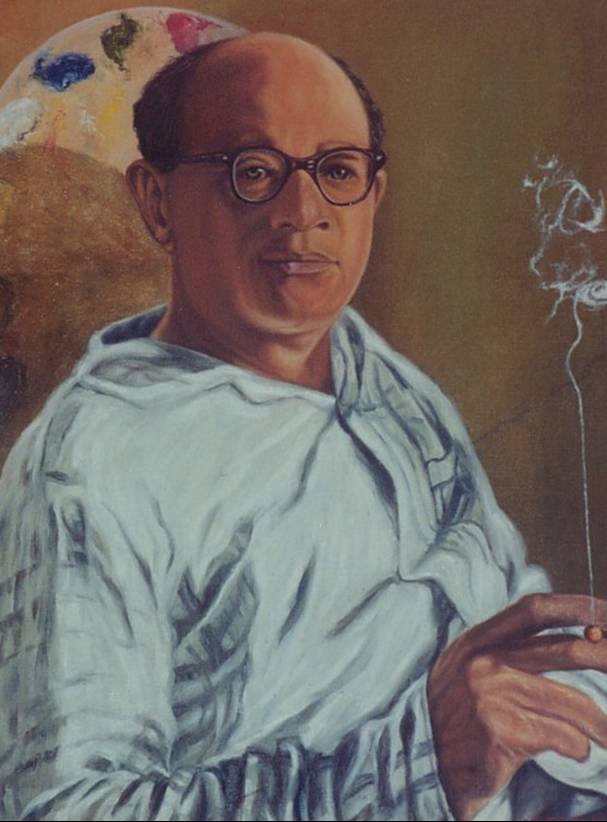

It is said that the greatest contribution George Odlum made to the nation was his raising of social and political consciousness and it is largely on that basis he is considered a candidate for the man of the century award. Well, if so, Allen Chastanet is in good company. For, as hinted above, he served as the lightning rod that raised the racial and nationhood consciousness of St. Lucians.

Allen Chastanet called our bluff. His rule made it blatantly clear that despite all our talk and slogans—simply beautiful, Helen of the West, Black is Beautiful—as Rick Wayne has been telling us all along, we are a people facing a self-confidence crisis, a national identity crisis, an existential crisis; a people with a heavy dose of self-contempt. A cultural icon said it best. He said if the Folk Research Center (FRC) had done its job properly, Allen Chastanet would have never become prime minister. Meaning, that despite FRC’s substantial contributions to St. Lucian heritage, it had not gone the full distance of helping St. Lucians understand and appreciate their history and of instilling in them a sense of identity. Of course, the assumption here is that having a White or an almost White as the prime minister of the country is a bad thing.

George Odlum with his theatrical flair and great appreciation for drama must be smiling mischievously from above. Because all that it took to bring to the fore the things for which he spent a lifetime agitating and advocating—the social and political empowerment of the masses; the notion that they are as deserving as anyone else of the best the island has to offer, that the country is there to serve them, that they can be as good as anyone else in any other part of the world—was for Allen Chastanet, an almost white man who culturally speaking is barely St. Lucian, to take the helm of government.

Suddenly, Philip J. Pierre minus the oratory power was sounding very much like George Odlum and George Charles. When Kenny Anthony came to power, in making sure everyone knew in no uncertain times that we were in the era of New Labour as opposed to Old Labour, he had placed several deputy prime ministers between him and George Odlum. Well, thanks to Chastanet, Phillip J. Pierre and the Labour Party have returned to the fold of Old Labour. Suddenly, in juxtaposition to Allen Chastanet’s perceived modus operandi, Philip J. Pierre’s Labour Party is voicing some of the obvious things that we needed to be doing to arrest our inferiority complex and self-contempt, to bolster our national pride and sense of nationhood.

Chastanet was perceived as putting foreigners first and taking from St. Lucians to give to rich friends, family, and foreigners. Philip J. Pierre countered with “putting St. Lucians first” and a promise to be “prime minister not for some of the people, but for all the people … (and to ensure) the resources of the state are used to benefit the majority of the people.”

Chastanet was perceived to be waging war against St. Lucia’s patrimony and educational system—closing Radio St. Lucia, downsizing and turning the St. Lucia Jazz and Arts Festival into an elitist affair, disrespecting and defunding the National Trust, causing the closing of the Derek Walcott House. Pierre drew the battle lines. As his first acts of government, he restored the funding of the National Trust, brought back the one-laptop-a-child program, and promised to plant a college graduate in every St. Lucian household.

Chastanet was accused of denigrating St. Lucians, treating them with disdain, making them feel they were less than others, robbing them of their St. Lucian-ness, referring to them as “barking dogs,” and “mendicants.” In brief, Chastanet was damaging the St. Lucian psyche; he was a Massa intent on revisiting slavery on the people. “Believes he is still in the days of slavery, that’s his problem,” said Philip J Pierre in Parliament as leader of the opposition. Pierre lividly pushed back. He pledged to make Emancipation Day a highlight of St. Lucia’s cultural life.

This government will make the first of August a major event in our national calendar. Our self-esteem, our dignity, our respect for the lives and struggles of our forefathers demand this of us… We pledge to fight against the mental, economic, and social attitudes that remind us of the terrible days of slavery and fight for a truly democratic society and equal opportunity for all…

And leaving nothing to chance, Pierre promised to “take steps to ensure that the African, Caribbean, and St. Lucian history is taught at all levels of our schools…” And taking a cue from Mia Mottley, he signaled his intention to replace the Privy Council with the CCJ as the court of last resort, and to get rid of the Queen of England as head of state.

It is no secret that SLP ran a whole election campaign without a credible vision for the country, and other than shouting Chastanet-Must-Go was very unconvincing as the party to advance the cause of St. Lucia. In terms of vision, conviction, confidence, and a semblance of where they wanted to take the country, Chastanet and his UWP had held all the cards. It appeared that Labour had lost its way. The party had run out of ideas and became unattractive, especially to new and young voters. The Party’s bread and butter slogan/philosophy and, according to UWP, propaganda, we are for the malaway, had apparently become trite and hallow, particularly against a confident and convincing Allen Chastanet who effectively countered the malaway philosophy with the interpretation that SLP’s malaway modus operandi is to keep the masses poor and dependent while the UWP way is to break the cycle of poverty and dependence by teaching the people how to fish.

The Labour Party had become so bankrupt of ideas and leadership, that the problematic but charismatic Richard Frederick, a reject of Chastanet and the UWP, a lawyer turned politician turned talk show host who is in the bad books of one or more foreign governments, became its defacto party leader even though he had never been and still isn’t a member of the Labour Party, prompting some political pundits to conclude that SLP had made a deal with the devil, had sold its soul, to displace Allen Chastanet.

Therefore, if Chastanet had been more circumspect, and had kept his eye on economic issues (the core of his election campaign platform) instead of interfering with the people’s culture and picking unnecessary fights with the National Trust; and if he hadn’t allowed Guy Joseph, who some regard as the most corrupt politician in the nation’s history, such free rein, instead of now warming the opposition’s bench, he might have buried SLP for a long time, and would have been talking about dynasty in the manner of his mentor, Sir John Compton.

Chastanet was the best thing to have happened to Philip J. Pierre and his Labour Party (with Richard Frederick and Stephenson King a close second and third). Chastanet and his political twin, Guy Joseph, enabled the landslide victory of an uninspiring and unconvincing Labour Party.

Allen Chastanet and the Second St. Lucian Cultural Renaissance

As far as one can tell, the administration’s main thrust is centered around the youth economy initiative and “putting St. Lucians first.” Any government which focuses on the youth of its country should be applauded, however, some suspect the Youth Economy to have been a campaign ploy, a sexy-sounding-youth-oriented phrase that presented Philip J. Pierre as a leader in step with the times and to distract from the fact that the Labour platform lacked credible vision and convincing leadership. Most of the elements of the youth economy that are being espoused were already in play under the previous two or three administrations, and we may need to thank the Taiwanese government, more so than the St. Lucia government, for any present youth economy impetus.

Putting St. Lucians First has become an SLP mantra, threatening to displace malaway as the predominant Labour philosophy, but it can hardly be characterized as a vision or plan of action and was yet another reaction to Chastanet’s rule.

Without Allen Chastanet, it is unclear what Philip J. Pierre and his government would have been doing.

Where the Philip J. Pierre administration seems to be scoring the most runs is in culture. Notwithstanding Chastanet’s complaint that St. Lucia would have been better served to keep the Dubai Expo focused on attracting FDI as he had originally envisioned, it was a great idea to add the cultural component and a beautiful thing to watch St. Lucian youths on the world stage. According to Export St. Lucia, even St. Lucian books were a hit at the Expo, attracting much interest and attention from even non-English-speaking readers, in part because St. Lucia was the only country that featured books as part of its exposition. Both the prime minister and the minister of culture, Dr. Ernest Hilaire, are promising to take Emancipation Day celebrations to the roof. This year the minister introduced monetary awards for calypso songwriters whose songs made it to the finals, signaling that the government is intent on leaving no stone unturned in encouraging the artistic expression of St. Lucian culture, in nation building, in bolstering the St. Lucian national identity. Dr. Hilaire’s agenda seems to be aimed at getting St. Lucians back to loving and respecting themselves, their country, and their countrymen. Bringing back, I feel good, chin up, chest out, and, as John F. Kennedy espoused, asking not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country.

Thus, George Odlum isn’t the only one smiling from above. So too is Derek Walcott, among other things a lover and practitioner of theatre arts. For years the great man advocated for more governmental and societal support for the arts. He lamented that the one strength of Caribbean people is their culture, yet governments continue to under-invest in art and culture, failing to fully exploit the benefits culture can bring to the region. Well, as a reaction to the rule of Allen Chastanet, it seems that Philip J. Pierre and Dr. Ernest Hilaire and their government are finally taking heed and making culture a key plank in their agenda for the country.

Life is so strange, so full of ironies. So many of our great thinkers—among them Harold Simmons (regarded as the father of St. Lucian culture), Sir Arthur Lewis, George Odlum, Sir Derek Walcott—tried to impress upon us, though with limited success, the importance of culture to our well-being, to our development. But all that it took to galvanize government support for the arts and placing culture on the front burner was the rule of Allen Chastanet, who culturally speaking is considered barely St. Lucian.

Many good things would come out of encouraging, nurturing, and promoting our culture. It would help stimulate the economy (especially the youth economy), diversify and solidify our tourism product, and strengthen and showcase our national brand, which will help draw good things to the country, including foreign direct investments. It would help give our lives as St. Lucian and Caribbean people deeper meaning and would help in defining, clarifying, and solidifying our national identity and sense of nationhood.

One suspects that the West Indies civilization is at a crossroads. The deeds of our past heroes (George Charles, John Compton, George Odlum, West Indies Cricketers of the 80s & 90s, etc.) and the wisdom of our prophets (Bob Marley, Derek Walcott, etc.) seem to have carried us as far as they could. One suspects it isn’t just St. Lucia suffering from a national identity crisis, but the West Indies as a whole is suffering from a civilization identity crisis. We are a floundering people, living without a higher purpose. The rising regional violence, the stoning of prime minister Dr. Ralph Gonsalves, may all be telltale signs of this crisis. There seems to be no one to turn to for leadership. Many of our political leaders are shameless in their willingness to do and say anything to win our votes, stay in power, and fill their pockets at our expense.

Yet, there is a need to redefine who we are as a people, what we stand for, to ascertain our net contribution to humanity, and what we are bringing to the world stage.

But there is hope. The problem may not be as intractable and impossible to address as it sounds. Help may already be on the way. The prime minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley, who seems to have emerged as the de facto prime minister of the West Indies, is providing a glimmer of hope. She is a real-life example of how to raise the profiles of our countries, how to strengthen our nationhood, how to erode our self-contempt, how to stand tall as a people, and how to best position ourselves on the world stage.

In forcing Philip J. Pierre and the Labour Party on this path of national and civilization identity strengthening, self-actualization, cultural assertion, issues that go to the very heart of our civilization, although an antihero and some may say a villain, Allen Chastanet has been a game changer and so he may well have been St. Lucia’s best friend.

Related Posts

Allen Chastanet A Blessing in Disguise

Aftermath: A Provocative Post Election Analysis of St. Lucian Politics

The Allen Chastanet Ultimatum Part 1

The Allen Chastanet Ultimatum part 2

Vieux Fort Political Leadership Crisis

The Youth Economy: Taking Stock

The Youth Economy: Culture as an Engine of Economic Growth

The Youth Economy: The Role of Government in Strengthening the Cultural Industry

The Motherland in Despair (Poetry)

The Kilimanjaro (Poetry)

About the author

![]()